Chasing imperfections

Are hands beautiful only when held in certain poses?

Hello and welcome back to shelf offering, a newsletter by me, Apoorva Sripathi – writer, editor, and artist. shelf offering is published three out of four Tuesdays a month, unless I’m taking a break. If you think my work is valuable and would like to support me, follow 💌shelfoffering on Instagram, share this post, and consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you.

What do you know of cooking by hand? Gently gripping ladles and spoons, stirring and tasting, mashing and lifting, sieving and shaking, chopping, dicing, slicing.

I know of two or more things. My mother reaching into the wet grinder to collect all the idli-dosai batter using her whole right arm, while her left holds onto the edge for balance and the right hand makes a clockwise motion to sweep all the batter into a large vessel. There is the vadai, paruppu or ulundhu (both are actually lentil-based). Paruppu asks very little of you, to form patties in one palm while the other shapes it into a disc before frying. Ulundhu demands more than participation, it requires a geography of the senses. The dough smells earthy, funky, and nutty when ground. Then your hands form a claw to froth it up, letting air into the batter, like the soap foaming inside a washing machine. Plop a spoonful of it into a glass of water to see it sink or float (latter is good). Add the required mix-ins: onions, green chillies, curry leaves, ginger. Now comes the hard part, the shaping. Ulundhu vadai shaping is elusive, at least for me. The batter is thick yet shifty, so you wet your hands just enough to handle it and then you roll it into a ball, the dough freewheeling inside your hand. After a few rolls, you poke a hole in the middle with the thumb and if you’ve done it right, you can slide the vadai easily into the shimmering hot oil.

This is where I fall short, where the vadai changes shape in my hand, sticks and stutters, and falls into a giant clump into the iluppachetti (wok). It still comes out crispy but it takes two, three, four, five, six, countless tries to get the shape right and with every try there is a structural repetition, a ritualised participation.

Have you seen the murukku, specifically the kai murukku? The murukku is a snack made with rice and lentil flours and spices, but the ingredients depend on the type of murukku you’re making. Some murukkus require a press which extrudes the dough into long lines which the maker twists (hence, murukku) round and round over itself to make a squiggly shape. The kai murukku (or hand twist) requires a specificity by hand, which means that the dough should be just wet that it’s pliable but not too wet that it dissolves upon touching the hot oil. Only those who have been twisting for years can truly master the shape, for everyone else it’s chasing imperfection by hand, they’re designs dictated by chance.

*

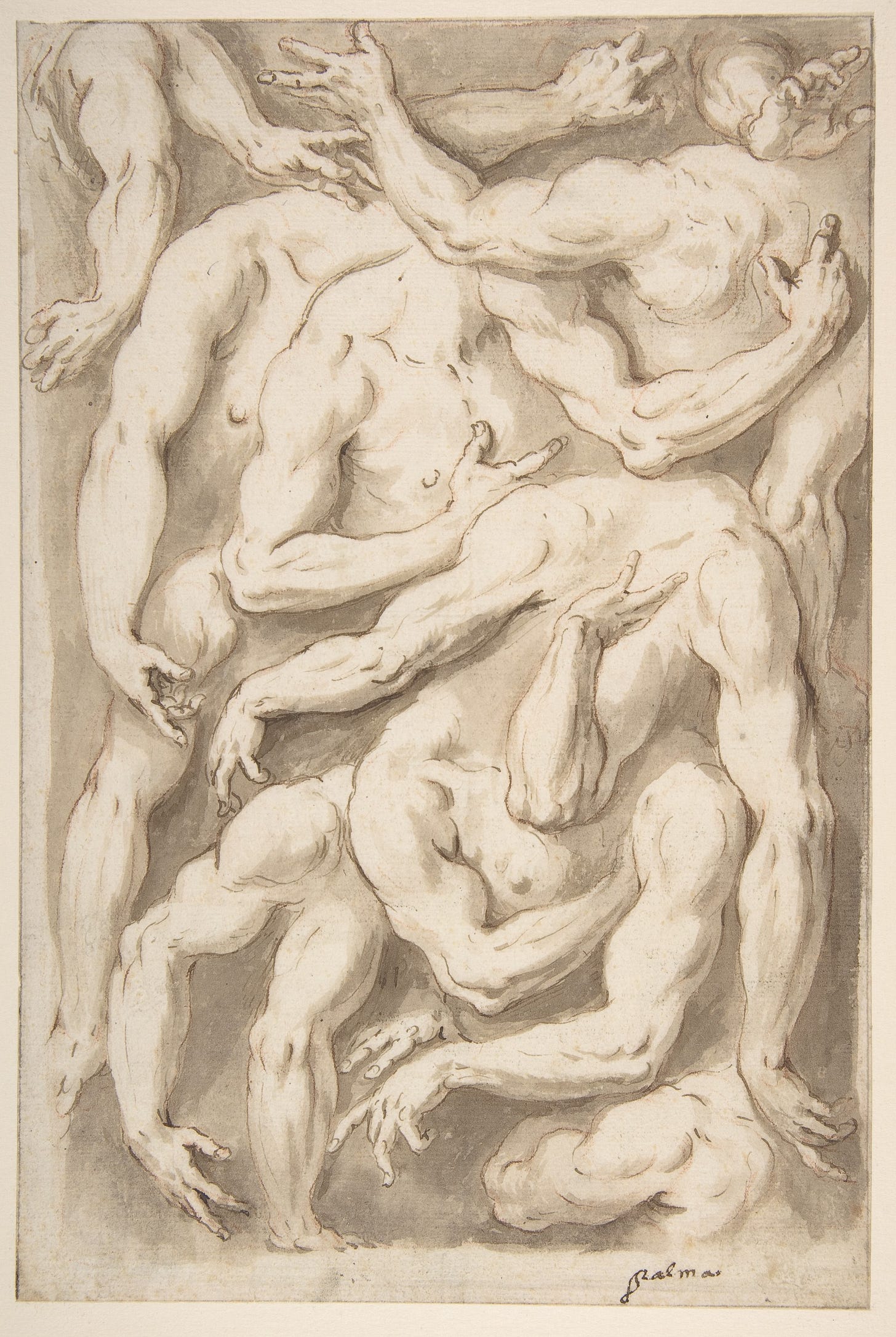

Are hands beautiful only when held in certain poses? Battista Franco’s red chalk sketch ‘Standing Male Nude with Hands behind Back’ ignores the hands (reminds me of my early life drawing studies) and places it behind the body. I imagine the left to be gently cupping his buttock, making a supportive claw while the right’s upturned without offering or receiving any such support. I’m not in the least bit religious but I wanted to also include here the sculptures of Sambandar, a 7th century poet-saint of the Shaiva tradition in Tamil Nadu, which are always cast with his right forefinger raised and pointing up to indicate the abode of Shiva and Parvati at Kailasa. This particular sculpture details his hand in fascinating, minute detail, with his right palm lines forming a parallelogram and his left palm slightly curled holding a bowl.

And then the clasped hands of English poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning by American woman sculptor Harriet Hosmer cast in the 19th century (there are several versions in bronze and plaster). Until I came across this object, I always thought of these casts as banal, particularly in those five minute content mill videos where everyone seems determined to make utterly useless objects. But this bronze object is so skilfully cast and feels intimate – another form of portraiture, one that is “a trace…like a footprint or a death mask,” as Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography. The inclusion of the cuffs and the wrists aren’t casts but rather a decision of the sculptor to include it to differentiate between the poets. They are an “obvious intervention in the casting process, products of an artistic choice that makes a critical contribution to the resulting sculpture. The cuffs act as a limit to the Brownings’ exposed skin, almost in a gesture of propriety,” writes Katherine Fein in The Sense of Nearness. There is a meticulousness in detailing the knuckles and the nails, wrinkles and pores.

*

I haven’t drawn hands in a long time but I have been thinking about them. I regularly think about my own, in particular my right hand and its wrist that suffers from a long-drawn injury and flares up every time I exert myself through its labours. Which is every day. Strangely, that hasn’t made me want to give it all up but instead strengthen it further – I don’t mean to romanticise vocations by hand but certainly the ones I undertake have some meaning to me. It is a ‘model of reality’, as Wittgenstein describes his creative process.

Part of my creative process involves watching a lot of YouTube (old Tamil movies and songs, recipes, vlogs, music, Nigella cooking, yoga and pilates when I feel like it, videos of people showing off their hobbies… this is an inexhaustible list). I came across this Italian cook making zucchine alla scapece, preparing to cut the pale green courgettes by hand into thin rounds. “Slice them into a thickness not too high not too thin,” – the video was in Italian and I ended up using a translator. “You could use a mandolin if you wanted and they would all end up perfectly thin but you could make them by hand, slicing them which takes not much.”

I took a shine to this concept of “not much”. I enjoy cutting vegetables by hand: I love how raw bananas give off a sticky sap in between slices, how potatoes can be severed so thin that they can become opaque films, how onions turn into both waxing and waning crescents, how the beheading of green beans is that of a practised restraint but the massacre of beetroot into fine dice, dyes my hands a stubborn pink. I love this act of slicing and dicing, chopping, cutting and severing so much that I inwardly challenge myself to slice tomatoes into thin membranes or to break cleanly the florets of cauliflower and broccoli. Using the knife may be a singular gesture but it there is a landscape of sounds that follow through: the crunch of greens, the freshness of a chayote, the squeakiness of ladies finger, the seam ripping suction cup squeal of a thick aubergine.

Equally, shortcuts are valid and there are days when a food processor makes this all worthwhile so I can get dinner on the table faster and my hands are preserved for something more precious and mundane, like writing or washing my hair. But the employing of a knife is gratifying, its siren call too strong for me to refuse, and before I know it I’m admiring the elegant, rigorous movements my hand makes when I rock it back and forth and up and down.