A lil announcement: shelf offering will offer paid subscriptions from next month, which means more essays and recipes, recommendations on what to read/listen/watch, and other new offerings. I’ll send more information in a newsletter sometime before the end of October, so if you love reading and want access to the other stuff, consider becoming a paid subscriber. I’ve managed to keep this newsletter free since 2020 but it’s no longer financially viable for me to do so. I will still send out free newsletters every month but if you’d like to support my work—and it’d mean a lot to me if you did—do give it a thought.

I’m very very grateful to everyone who’s supported my work so far by subscribing, sharing, commenting, liking, and even thinking about my words. It will only get a lot better going forward! No pressure to anyone who cannot, my words are still available, so thank you for the honour. The main reason I started writing this newsletter is so I could arrange all my incoherent, random, diffusive thoughts into one messy pattern, and to create work on my own terms. Essentially to display my weird self for the internet to take a look at 👀. Thank you for being here!

I have been envious of ‘tomato girl summer’—the food season, not the fashion trend—because of the sheer diversity of tomato species up for grabs, available only for a particular period of time and highly coveted. It echoes ‘sensual mango summer’—although my summers are more jarringly sensory than sensual—that highly sought-after season in the country where everyone goes nuts for their fav mango. Every person you know, who has grown up with a culture of mangoes, will have their favourite even if it doesn’t align with the popular rankings on twitter dot com.

But nothing intrigues me more than ‘pumpkin spice fall’ and the accusation that it is basic. Pumpkin spice—a mixture of spices such as cinnamon, cloves, ginger, allspice, nutmeg—is foremost a colonial project dating back to the Dutch East India Company and is far from basic. Some of these spices are native to the erstwhile Spice Islands, today known as the Maluku Islands, and along with the others were available to Europe through trade routes via Alexandria via Asia. Spices harvested in Asia became a symbol of wealth in medieval Europe as the high society had “an insatiable appetite for spiced sauces, sweets, wine, and ale”. Sarah Wassberg explains in her blog The Food Historian that when the Ottoman Empire took back control of the spice trade from the Europeans, the latter “simply took what they wanted by force”—the Dutch colonists committed genocide to secure a monopoly on nutmeg.

Maybe my yearning for pumpkin spice fall comes from the fact that where I live doesn’t really have a pumpkin season or fall/autumn. I only know of endless summer and reluctant monsoon! Cucurbitae, as the gourd family is known formally, is large, containing close to a 1,000 species. From this family, emerge the genera cucurbita, lagenaria, citrullus, cucumis, momordica, luffa, and coccinia, which are some of the most important ones known to us humans. Actually, make that vital. Gourds have not only fed and nourished us but they’ve also been a part of the way of life, finding use as musical instruments, natural sponges, bowls and containers, art and culture. So not just who are we without pumpkin spice, but also who are we without gourds?

Gourds are testament to significant nuggets of history; incidentally, they’re also edible. The calabash or the bottle gourd is special to Nigeria, a creeper plant that grows almost everywhere in the country. It’s no surprise then that the hard shell, dried, is purposed into bowls etched with tiny animals, peoples, and abstract motifs—the decorations reflect the traditions of the area. These bowls are used as utensils to clean rice, carry milk, or store water/wine/food. A 1974 piece from Penn’s Expedition Magazine records that the empty calabash shell is turned upside down to be used as a stool for sitting down at the marketplace; as spoons and rattles; as bowls decorated for tourists; as head coverings to protect babies from insects and the heat; as butter churns; and even lampshades. Calabashes have to be more important to music than food, from the Yoruba percussion instrument shekere and the West African stringed instruments kora, xalam, goje (similar to lutes) to the gourd flute hulusi in China, Vietnam, Assam, and the Shan State, and as a resonator in the sitar, tambura, and the veena in India… and even as banjos and marimbas, the possibilities are endless.

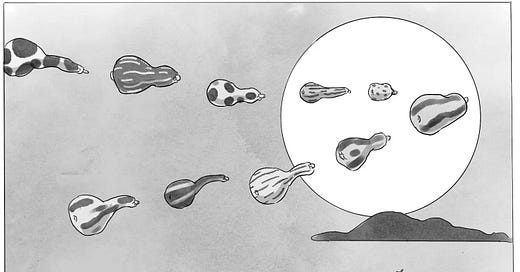

The history of how they spread throughout the world is equally, if not more, important. And also dare I say, cute. The question that seemed to peeve scientists for years was if gourd migration (yes, it’s a thing), specifically bottle gourd1, was by land or by sea. The calabash was one of the first cultivated plants in the world, domesticated as early as 10,000 years ago in the Americas, and also been found in China and Japan about 8,000-9,000 years before present. Its original home is Africa, and the bottle gourd reached East Asia before being distributed to the Americas through sea. In 2005, a study overturned the previously held belief that the gourd had been diffused through human mediation and that there was proof that it was carried instead by ocean currents. The study found structural similarities between “present-day bottle gourds grown in Africa and the Americas”, and therefore the “substantial majority of researchers writing on the topic over the past 150 years have formed a consensus that L. siceraria [bottle gourd] reached the Americas by ocean currents directly from Africa”.

Because I have a penchant for edible floats2, I was reminded of the great coconut migration while researching for this piece, as some historians claim that the coconut could’ve floated its way to India3, hardy enough to withstand typhoons and tsunamis. Both the histories of coconuts and gourds are interwoven with that of people and migration. Coconuts have been valuable travel companions because they’re sources of calorific food and potable water packaged in an eco-friendly, spill-proof vessel. You can make both sugar and alcohol from it, ropes and fibre from coir, oil from the nut, and burn the shell for charcoal. Along with the banana and the gourd family, they’re the definition of abundance. And since they’re found everywhere, retracing both the coconut and the gourd’s steps are near impossible.

Gourds are prime vegetables for the ‘no waste’, ‘scrap cooking’ trend. A hard outside and fleshy inside might indicate limited usefulness but the ingenuity lies in using both the flesh and the skin. There are numerous recipes online for gourd skin thogayal/chutneys that the subcontinent is well-versed in. The ash gourd makes for excellent candy, halwa, stir-fries, soups and stews. Coccinia grandis or ivy gourds are the equivalent of fingerling potatoes that find a place in the Thai curry, kaeng khae. They’re also great as pickles, in sambar, and deep fried with spices. The snake gourd or the Trichosanthes cucumerina which is unusually long (and is very satisfying to cut and empty the spongy insides) is lovely stir-fried with onion, spices, and grated coconut. And then there are the other suspects: cucumber, luffa (loofah), melons, pumpkin, and squash that are more popular than my newsletter so it’s rather pointless to write more about them.

The one gourd that is missing from the list is the bitter gourd/melon, which I think is the true Halloween gourd than the pumpkin, solely because of its gnarly, warty, slime green appearance, and a bitter taste that is sure to put the fear into both children and adults alike. It is indeed a rite of passage for some—if you were a child who ate it no questions asked, then you’re the type4 to patiently read all the terms and conditions—only making peace with the vegetable as adults. It took me 31 years but I finally enjoy it now.

Gourd thogayal

1 small-medium snake gourd, or a ridge gourd

2 tbsp chana dal

1 tbsp urad dal

5-6 dried red chillies

a handful of curry leaves

1 small-medium onion; substitute with 4 pearls of garlic

1/3 cup fresh grated coconut; substitute with a tablespoon of peanuts and a teaspoon of sesame seeds

2 tsp tamarind paste, or a small pinch of tamarind (the size of a tiny gooseberry)

salt to taste

Wash the snake gourd and chop into two horizontally. Split each piece lengthwise to scoop out the soft insides and the seeds. Chop the two pieces into smaller pieces and set everything aside, as you can use all of it, seeds included. If you’re using a ridge gourd, peel scantly to get rid of the ridges and chop into smaller pieces.

In a pan, heat some vegetable oil and add the onion. Fry till golden, then add the chana and urad dal. Once golden and fragrant, add the chillies and the curry leaves. Fry till the curry leaves lose moisture. Add the tamarind, coconut, and the gourd and saute for a minute. Let everything cool before you blitz in a food processor along with the salt and grind to a coarse paste. Add a tablespoon of water only if you require. You can add a pinch of jaggery/brown sugar before grinding. You can serve this with hot rice, dosai, chapati, or even on hot buttered toast.

Miscellaneous

Work has been stagnant everywhere and I have nothing published yet. I’m looking to pick up editing+writing gigs, so if you’re an editor reading this and you like my work, please get in touch.

Alongside pitching and courting rejections, I’ve also been experimenting with writing short stories and poems. Had no time to read anything for leisure sadly! Words are jarring to my eyes! Please let me know what you’ve been reading, would love to hear from you.

The bottle gourd is known as sorakkai/surakkai in Tamil and a wonderful expression that comes from this vegetable is ‘surakkai ku uppu illai’ which means that the ‘bottle gourd lacks salt’, and is used to express annoyance/dismissal of something that’s meaningless.

I’m referring to the time when as a teenager who reluctantly went to tuitions, I sought refuge in vanilla coke floats at a nearby bakery that’s sadly no more!

The Tamil word for coconut, thengai/thenkaay, can refer to both ‘a honeyed (raw) fruit’ or a ‘fruit hailing from the south’. I know Tamil Nadu is already in the South but it points to the direction of where the coconut comes from, which is further south.

No shade at all, I’m just envious at your keen sense of discernment!