Hello old and new subscribers—welcome! If you like this newsletter, follow 💌shelfoffering on Instagram and please share with a friend or two.

‘They steal your bread, then give you a crumb of it.

Then they demand you to thank them for their generosity!

O their audacity!’

Ghassan Kanafani, Palestinian author and poet

—

'Gaza is starving' reads the headline of an Isaac Chotiner piece for The New Yorker, which strangely does not mention who is responsible for the starvation. Neither does the subhead delve into why this is happening, instead focusing on how this starvation “may tip the territory into famine”. The lede goes into detail about the “catastrophic” situation in Gaza,

where more than ninety per cent of the population has been facing “acute food insecurity,” and where “virtually all households are skipping meals every day.” Much of Gaza is at risk of famine in the next several months. Parents have been going without food to insure that their kids have at least something to eat…

Not one line, however, mentions the forced starvation and the genocidal campaign by Israel in Palestine. Are we simply supposed to reason that the people of Gaza have been starving themselves? As Jon Randell Smith writes, “genocide has a long-standing relationship to food, specifically intentional starvation and famine.” On the one hand, the United States, a complicit partner in this genocide, airdrops 38,000 meal packs, while the other hand provides Israel with ammunition, and funds to sustain this genocide. As if a mere 38,000 expired meal kits could sustain the more than 2 million starving in Gaza. (Even as trendy media outlets write calculated pieces on why pomegranates, a symbol of Palestinian resistance and culture, don’t need a comeback.)

I’m reminded of a Tamil saying1 that goes “the left hand should not know what the right hand is giving2”, alluding to being so charitable that even one hand of yours does not know how generous the other one is. Except in the case of the United States, it’s about being performatively lavish for the wrong reasons. It has to be nothing short of a cruel joke to say that Gazan households are “skipping meals every day”, because they are intentionally being starved, even prior to October 2023.

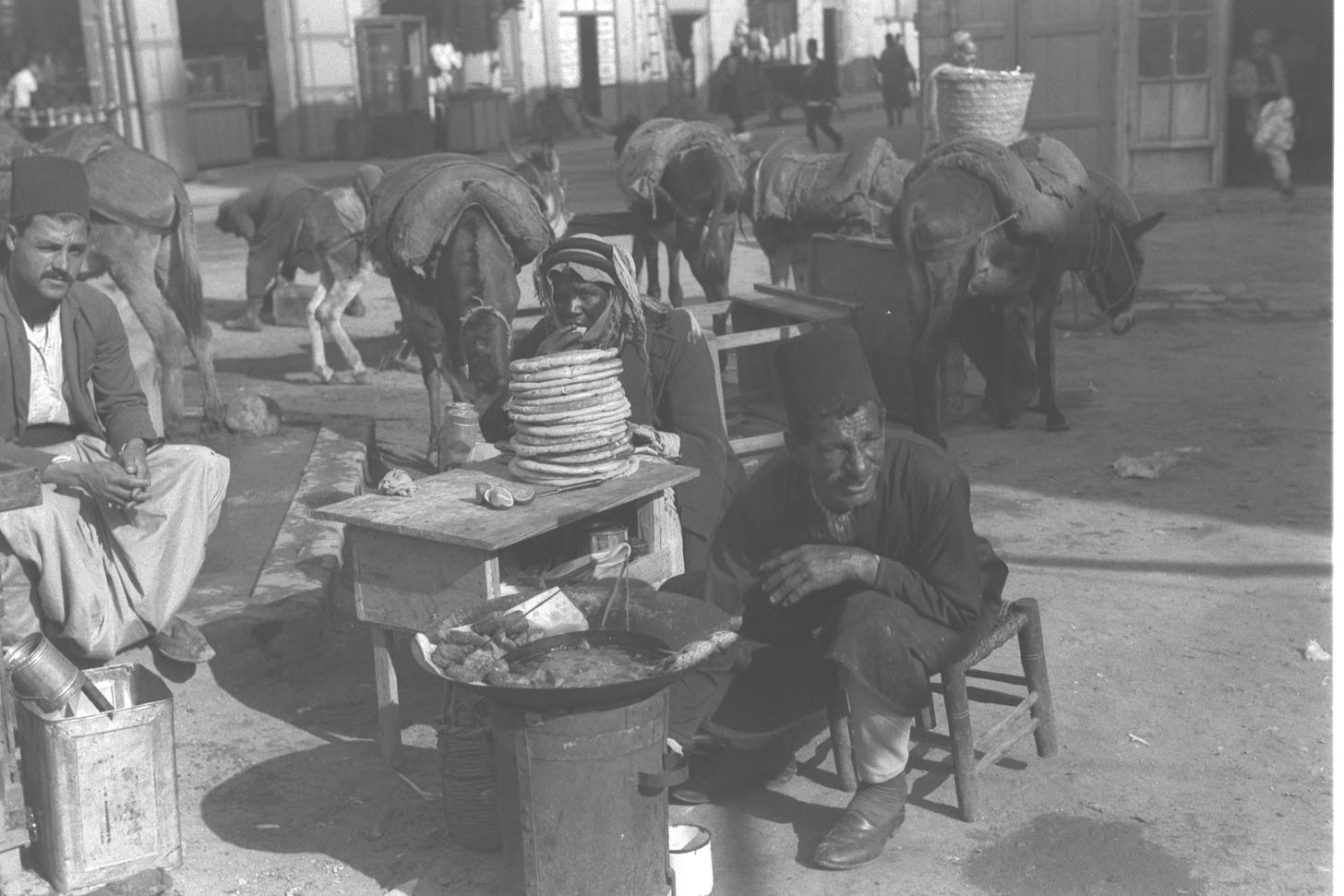

On 29 February, more than 100 starving Palestinians were killed by Israeli troops when they were trying to access aid, which is now (horrifically) known as the Flour Massacre. Those Palestinians who are able to feed themselves (and others) have been making bread out of animal feed, bird seed, and grass. Two weeks ago, the UN World Food Programme paused what they called “life-saving food aid” to northern Gaza until “conditions are in place that allow for safe distributions”. Will the conditions ever be safe?

For years now, Israel has consolidated complete power over Palestine’s water resources, including making it illegal to collect rainwater for domestic or agricultural needs, restricting access to water, or constructing “any new water installation without first obtaining a permit from the Israeli army” aka no new wells or water pumps. The ghost list of items that aren’t allowed to enter Gaza include anaesthesia machines, dates, oxygen cylinders, crutches, solar panels, ventilators and water purification tablets. Since 1967, Israel has destroyed 800,000 olive trees in Palestine. while settlers routinely block humanitarian aid entering Gaza. Bakeries have been bombed, boats bombed, trees bombed, aid bombed. White phosphorus has been sprayed on Palestinians, which adversely affects agricultural land, pollutes the groundwater, and weakens the soil. How do you begin to replenish, literally, scorched earth?

To make a nation, to create and establish it, to define it, food is often used as a tool. Just as national identities are sustained and reproduced using nationalist sentiments or boundary politics, national cuisines are seldom manufactured in a vacuum. They’re shaped by concepts of tradition and authenticity, valorised by the cultural prowess of the foods in question. It’s an exercise in futility, and a laughable one at that, because foremost it is a project of collective identity which has to be manipulated and constantly recreated on an imperceptible level. Remember actor Mayim Bialik tweeting about “a strong desire” to eat falafel at “an Israeli restaurant with Israeli rock blasting”, while turning off replies on her post? Or this person tweeting that the “popular Israeli couscous salad with spinach and tomatoes” is being renamed in the dining halls of Yale without the word ‘Israeli’? Which turned out to be a lie. Does nothing make sense anymore?

Or maybe everything makes sense, depending on how you look at it.

Falafel is not Israeli. Its origin is contested as with most foods that have a shared history, but it is said to hail from Egypt, in Alexandria. Falafel reportedly comes from ful, Arabic for fava beans that were once the main ingredient. Meanwhile, the problem with Israeli couscous is that it doesn’t exist. Couscous does, dating back to the 3rd century, and it is a traditional North African food made from semolina. A staple in Maghrebi cuisine, it entered French and European cuisines only because of the French colonial empire. Israeli couscous, like the country itself, was newly birthed in the 1950s at the behest of David Ben-Gurion, then the prime minister, and by the Osem food company to feed the masses. What the world knows as ‘Israeli couscous’ is actually ptitim. This piece by Leah Koenig notes that “Osem was tasked with devising a hearty starch that was more affordable than rice…” and the company responded by making ptitim (meaning little crumbles) from wheat made into paste, extruded like pasta then dried and toasted. Originally, these were in the shape of rice, but the company made it spherical to resemble maftoul, “a pearled Palestinian couscous made from bulgur and wheat flour”, and “farfel, the petite, toasted egg noodles favoured in Eastern European Jewish cuisine”, so it could resemble couscous.

Jaffa oranges or Shamouti oranges, that are so interchangeable with Jaffa cakes in the UK, were developed by Palestinian Arab farmers in the 1800s and exported to Europe in the 1850s. Exports reportedly grew from 200,000 oranges in 1845 to 38 million oranges by 1870 after an export firm owned by the German Templer Colony, who settled in Palestine, was the first to use the brand name Jaffa in 1870. Middle East Eye reports that the Nakba, which dismantled Palestine 75 years ago “through the destruction of 500 villages, the forced exile of half of the Palestinian population,” gave rise to the loss of Palestinian industries and eradicated “important social and cultural traditions that united Palestinians”.

Bir Salem, located in the Ramle subdistrict, was one of many Palestinian villages that produced the famous Jaffa orange, developed by Palestinian farmers in the mid-19th century. Citrus manufacture in historic Palestine was one of the leading industries, with the Jaffa orange dominating global markets, making it the main export by 1900. By the 1930s, the citrus industry consisted of 77 percent of the total value of exports from Palestine.

For many Palestinians, oranges might have been their first taste of joy, culture, abundance, resistance, and resilience. Today, it has become a Zionist symbol of theft and appropriation. What is more fundamental to people and their culture than food? Especially when a country and its citizens are being violently uprooted, continuously for 75 years, while their cuisine is absorbed by the coloniser and rebranded as their own. Food has long been used as a tool of colonialism3, whether it’s Israel ‘foodwashing’ falafel and hummus, Europeans who forcefully introduced new foods into the diets of Native Americans, pumpkin spice lattes that derive from a history of genocide to simply establish monopolies on spice trade routes, or white Germans making TikToks about “discovering” tropical fruits with supposed childlike wonder.

The politics of culinary Zionism isn’t a battle for pride of cuisine; it is continuously bound up in appropriation, identity, and in the creation of a political project. The ownership of say falafel and hummus or Jaffa oranges is in actuality the ownership of land without any acknowledgment of origin. It is a project of nationalisation, of belonging, of cuisine as commodity, even as Israel gleefully destroys olive trees in Palestine, starves Palestinians to death, massacres Palestinians while gathering aid, films TikToks making fun of Palestinians suffering, cuts off water supply in Gaza, threatens bakeries from opening, claims rainwater as sole property, builds border walls in their apartheid regime and restricts movement of humans, interferes in local animal migration patterns, and in general uproots life. In short, it is a construction project of a violent nation, its agendas and borders, which require theft of culture and identity via food.

This essay was edited by Susanna Myrtle Lazarus

Miscellaneous

A Palestinian feminist reading list via Feminist Press.

My friend who edited this piece tells me that it's also a Bible verse, Matthew 6:3: But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing.

இடது கை கொடுப்பது வலது கைக்கு தெரியக்கூடாது

And nationalism.

As always, a superb piece.

This is so good. And the callback to the pomegranate bs article 👏👏